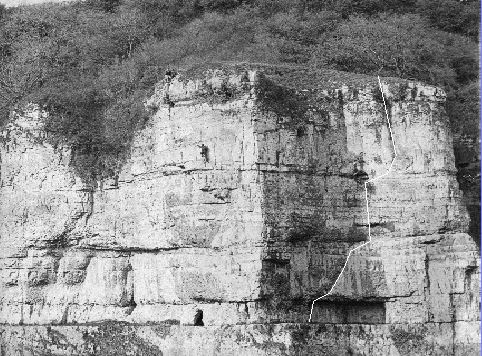

Rock Climbing at Stoney Middleton in the 1970s

ROCK-CLIMBING AT STONEY MIDDLETON IN THE 1970s

Personal recollections of the 1970s by Geoff Birtles

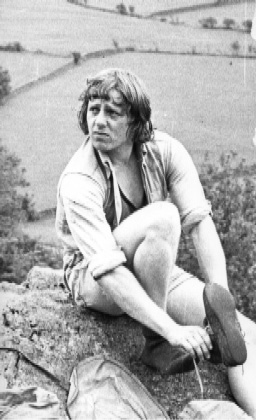

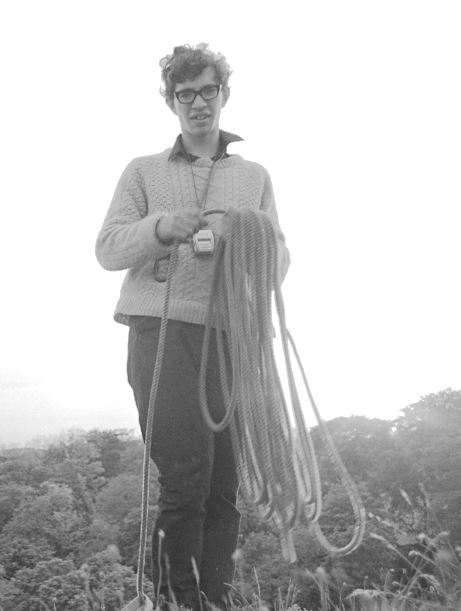

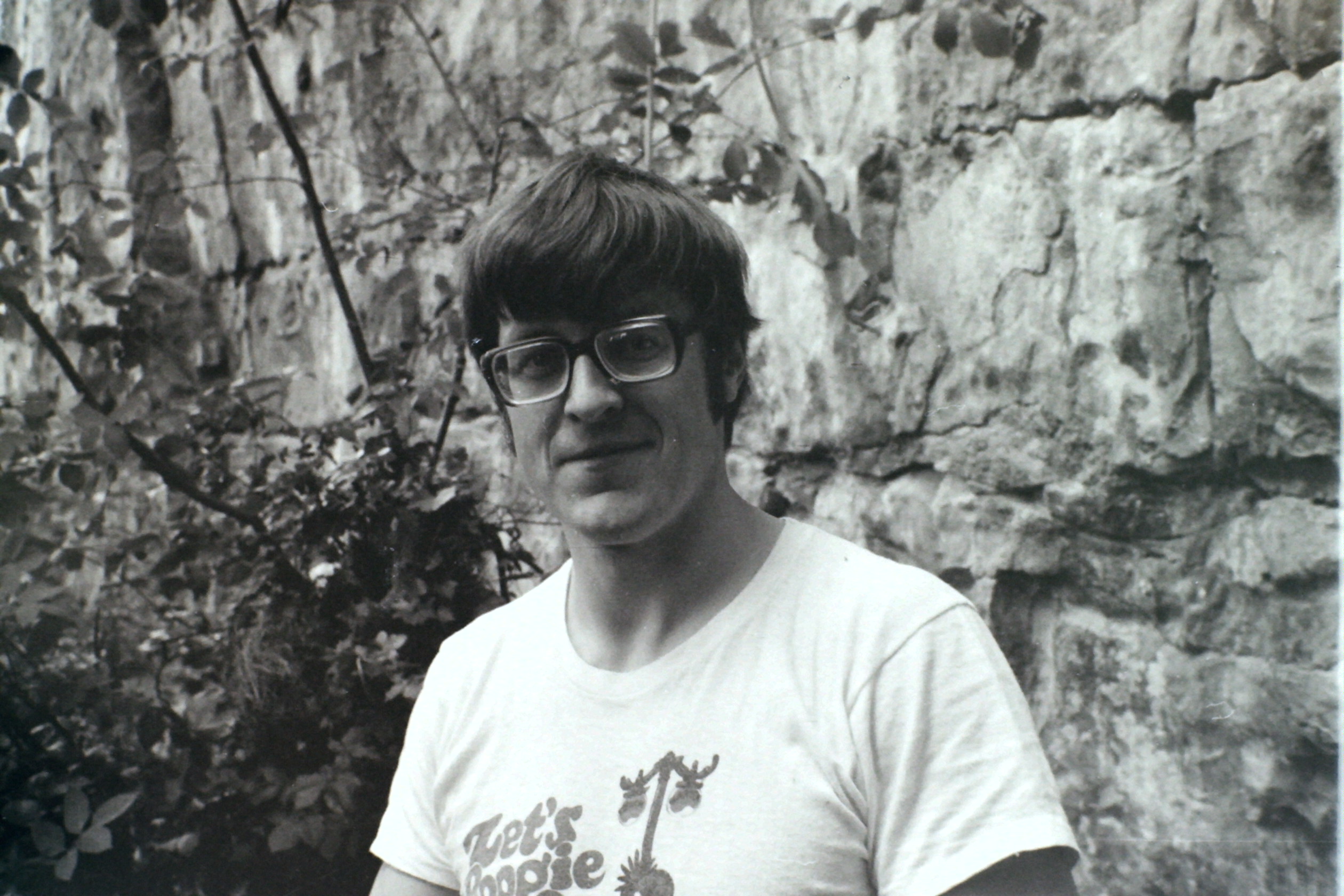

All histories are versions of events and this one is no different. Following are some personal recollections of climbing at Stoney Middleton in the 1970s and a tribute to Tom Proctor (pictured below). Thanks go to others for their contributions, in particular from the late Paul Nunn archive , Keith Sharples and Mick Ward. As these come from a variety of sources, some items are duplicated, sometimes with a different slant which have been left for the reader’s discernment.

THE 1970s

Once upon a time, there was a young lad called Tom Proctor, a doyen in the subtle art of apparent naivety. He grew up on a dairy farm on the Peak side of Chesterfield and was within easy cycling distance of the crags. He had first ventured to Stoney, pot-holing as a schoolboy then later discovered climbing at Birchen Edge which was almost on his doorstep. Sometime later, he ventured to Stoney where he found our vibrant Cioch scene and, playing the innocent, would come into the cafe and ask for a good route suggestion. I recall suggesting Quietus at Stanage and what seemed like an hour

later he re-appeared in the cafe saying: “Done that.” He then did the same with Sentinel Crack at Chatsworth and so on and thus caught our attention. At some point around this time Tom also soloed The Flakes trailing a rope. I was never quite sure what good the rope would be nor if he belayed himself for the awkward final traverse move which at that time used a sling on a peg for aid. The Flakes then was still a fairly highly regarded route but more relevant was its exposure and, of course, unreliable limestone holds, so the achievement was quite impressive. I didn’t realise then that Tom would become my longest and closest climbing partner. I liked having a regular climbing partner for the best reasons in that you need to have a trust and understanding with somebody at the other end of the rope.

For example, and nothing to do with Stoney whatsoever, one day in 1977, I was with Al Evans on the 2,000ft South Face of Osant at the head of the Hardanger Fjord in Norway. This would be the first rock climb in the area. We were about 1,000ft up and as I set off to follow a pitch, Al shouted down: “Don’t fall off.” It was a sobering statement but I understood what he meant, that he didn’t have a reliable belay. It was off-vertical and the climbing was steady so from his foot ledge he could have given me enough tight rope if needed. That wasn’t the problem, that would come when I led out from him when, if I fell, I would rip him off and we would both be gone. So the trust worked two ways. As it happened, after about 15 feet I reached an overlap and from an undercling reached round and managed to place a good horizontal hex. It was a phew! situation. Had we needed it, the nearest mountain rescue then was in Scotland.

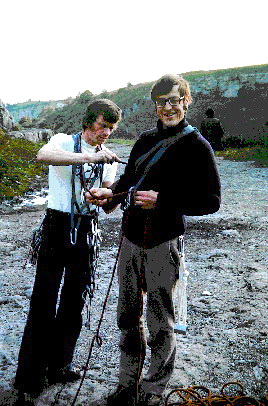

I digress but some years before this, back in Stoney Middleton, I’d had two main partners; Jack Street and Chris Jackson. Whilst Jack was still climbing exceptionally well, his interest at Stoney was waning. Chris was by now off somewhere else as he was always the most adventurous of the Cioch and had found some new grounds and new friends. About this time, I partnered up with a climber called Bob Keates though not so much for climbing but for a book project about the Peak District. I would do the writing and set up climbers and suitable routes and he the photography which is why there is such a good photo record of this period. Bob was an amenable fellow at Peterhouse Cambridge at the time reading Chemistry.  His full name was Robert Anthony Butler Keates, named partly after his relative, the noted Rab Butler, a distinguished government cabinet member from the early ‘60s so, whilst he could slob around like the rest of us he was a lot posher. After graduating, he continued his studies, now in Biology, for a PhD at Glasgow where he took on the study of butterbur, better known to climbers as giant rhubarb which grew in abundance in the limestone dales of the Peak and was noted for certain medicinal properties. This allowed him the excuse to be away from university for extended

His full name was Robert Anthony Butler Keates, named partly after his relative, the noted Rab Butler, a distinguished government cabinet member from the early ‘60s so, whilst he could slob around like the rest of us he was a lot posher. After graduating, he continued his studies, now in Biology, for a PhD at Glasgow where he took on the study of butterbur, better known to climbers as giant rhubarb which grew in abundance in the limestone dales of the Peak and was noted for certain medicinal properties. This allowed him the excuse to be away from university for extended

spells when in fact he was photographing us lot with his Leica and in particular a wide-angle 28mm lens. After university he emigrated to Canada from where he now recollects: ‘I soon became the Hitchhike King and could do the run from Glasgow to Sheffield almost as fast as you could drive it.

There was a derelict house on the quarry side opposite the Stoney crags where I could get a couple of hours kip before ‘you lot’ showed up. I had a bit of time on my hands between Cambridge and Glasgow and sometimes ended up with Jack Street laying carpets so we could finish early enough to get on the crags in the afternoon. I had a white sweater which my mum made me promise that I would never wear climbing, but the promise didn’t extend to others wearing it climbing and it made a nice contrast against the dark grit. Apart from the photography, I was happy to take the blunt end of the rope from time to time.’

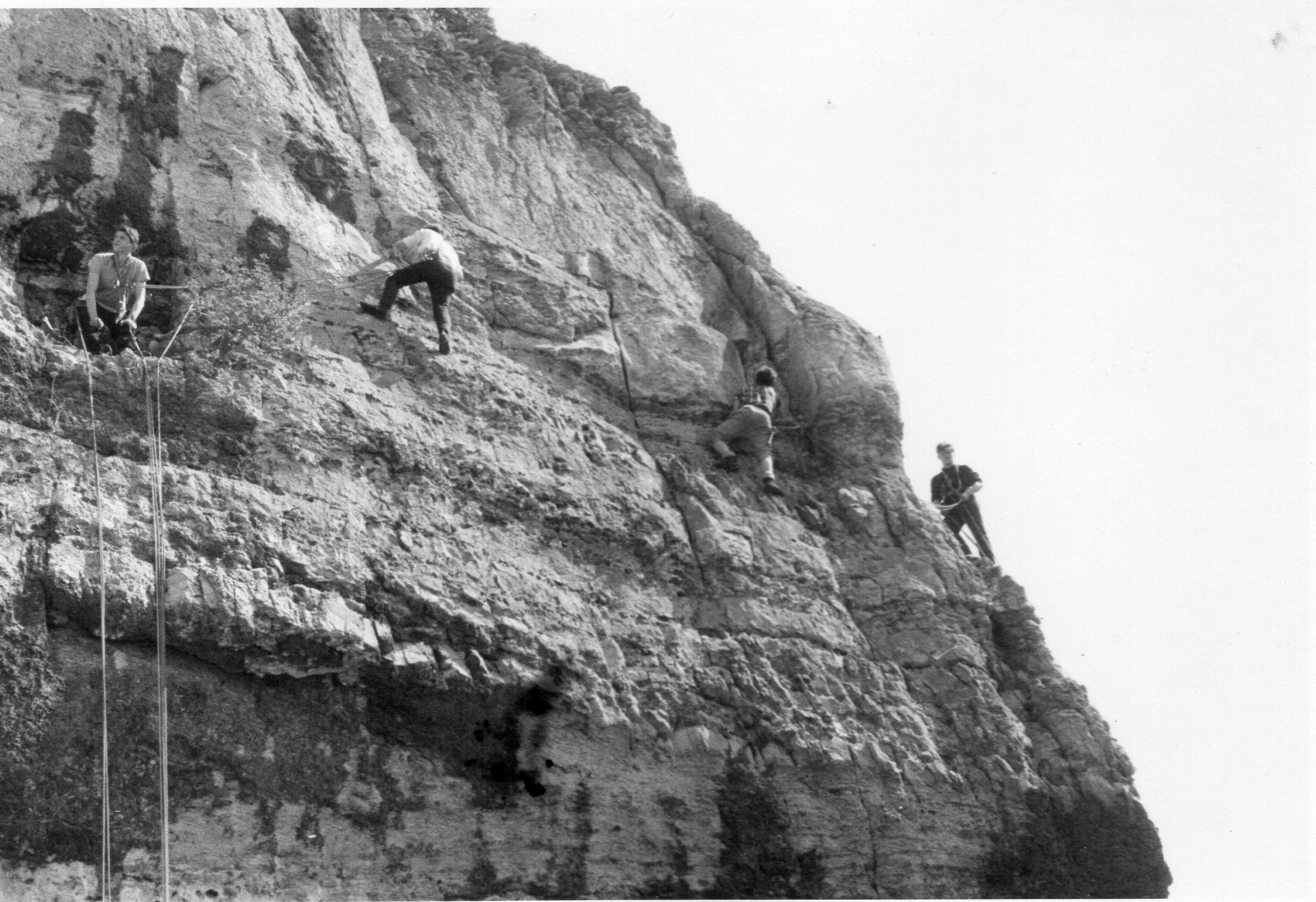

Basically, we, the Cioch, went round repeating all the classic Rock and Ice classics plus some of our own so that Bob could get the photographs which gave us a lot of pleasure and direction.

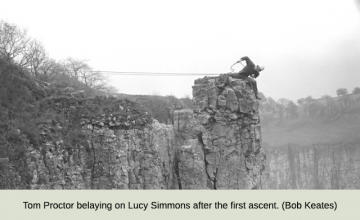

Lucy Simmons

One day, in January 1968, I went to the foot of The Tower of Babel with Bob Keates. I had my eye on the front face of the pillar and suddenly Tom appeared at the foot of the crag and so began a whole new adventure with Tom though I did have previous experience with him from the summer before when he had been doing the first free ascent of Zeus on Burbage South and was doing well until he couldn’t quite manage the last move. So, whilst Tom was stuck, I went up to the ledge above him and rather foolishly leaned down and offered him my hand though I had no belay and was just hanging on to a handhold.

He took my offer and pulled on to the ledge. Back at Stoney, on The Tower of Babel, Tom and I soloed up the lower chimney section to a belay and from there I climbed part way up Sin and placed a runner, then climbed back down and ventured on to the front face. I was leading on-sight with no more protection likely. The moves were not too hard made easier by using the edges of the pillar for either side-pulls or heel-hooks until I got to the last break very close to the top where I was in for a big fall should I fail. The last few feet bulged above me and my arms and maybe my bravery were tiring which made my mind up to traverse left into the top of Sin. It was still bold but nevertheless disappointing and I soloed down Glory Road to rejoin Tom who then took his turn reaching the top for a magnificent achievement.

As I followed and got to the point where I had traversed left, I reached up and there was a big jug followed by the top. Had I known I could just as easily have finished the route on my lead. I congratulated Tom and he replied: “I top-roped it last week. Stunned, I said: “You never told me that,” and he replied “You never asked.” When I said earlier that his innocence was not all it appeared, this gives you some idea. “You never asked” became a standing joke with us for decades to come.

I called it Lucy Simmons after a model on something like a Pirelli calendar. RockSport reported in its November 1969 edition: ‘Ed Ward-Drummond has made the second ascent of Lucy Simmons, a climb which has been avoided by local experts on account of its dreadful reputation.’

Our Father

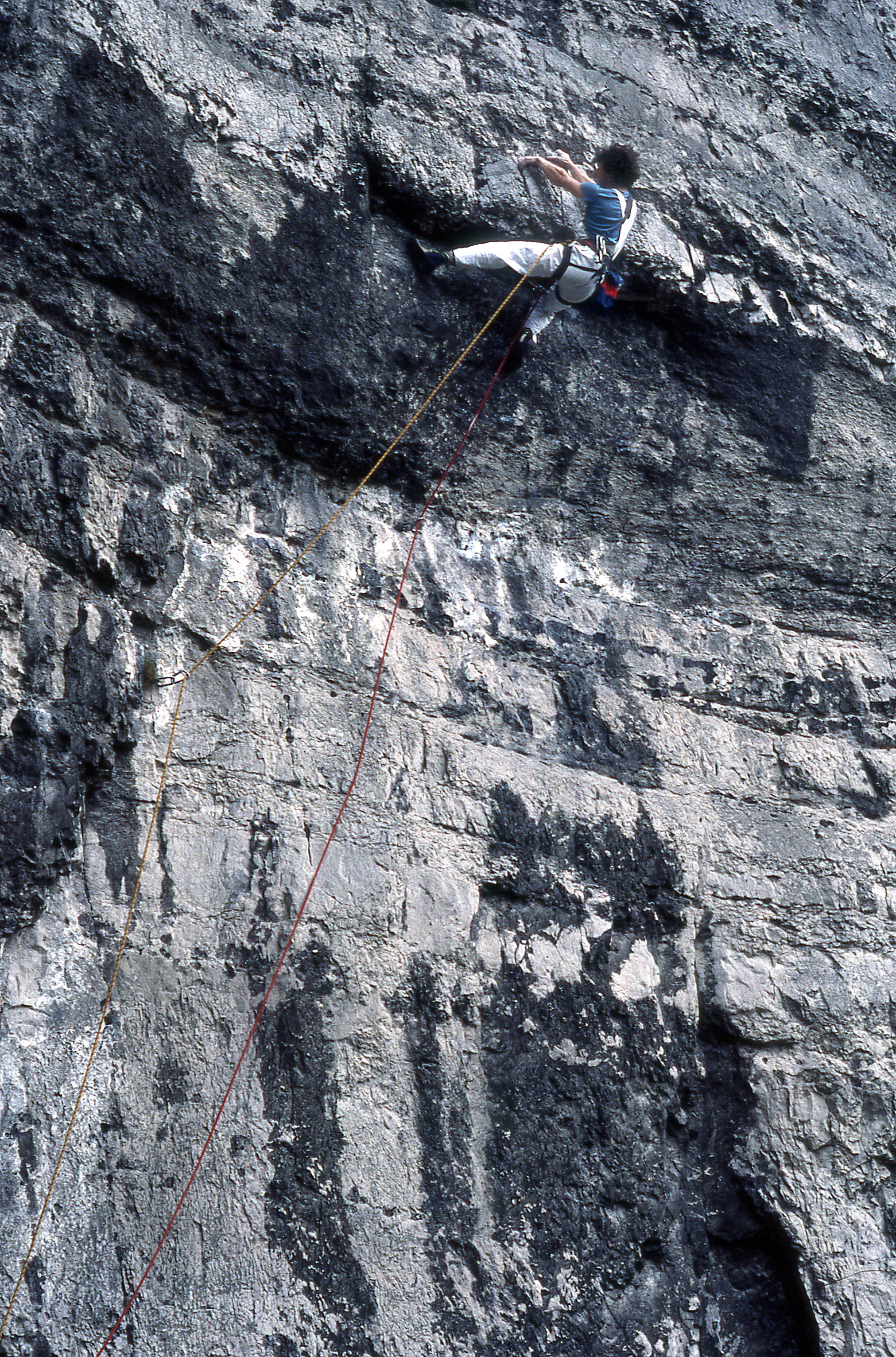

Tom and I climbed regularly as a team from then on and even grabbed a plum new route, Deygo, on that wonderful Anglesey sea cliff, Gogarth, in the April, regarded as the hardest route on the crag at that time. Then, in June ‘68 of that summer, Tom asked me to meet him one mid-week evening which was unusual in those days. He took me up to Windy Ledge and pointed up at the rightward trending flake to the right of Scoop Wall. I think it had either been climbed or tried on

pegs but whatever, it was off the scale of anything I’d ever seen considered for a free climb. This time he did admit that he had abseiled it, inspected the moves and placed two pegs and a fixed sling runner.

This approach to what was a new level of free-climbing became quite common if not the norm from about that time and it was Tom who was breaking existing mores to raise the barrier. He set off, up the lower wall to the roof, leaned backwards, placed a jam in the roof crack which enabled him to reach out backwards and over the lip where a layback flake enabled a gymnastic swing out to place a foot on the wall above. From there

it was a case of laybacking the flake to a peg runner, a peg remained for some 30 years and was beginning to look rusty. Years later, when we did the climb again for a television programme when Tom arrived carrying a ladder and nonchalantly went up and removed his own peg which, in fact,was absolutely fine and the rust was just superficial.

Nevertheless, he replaced it with a new one and then re-enacted those classic moves. Meanwhile, back in 1968, Tom stepped right from the peg to another one and then climbed up the steep wall above for a few moves to an underclung flake where he had left a threaded sling. The next move involved a jam under the flake which looked likely to fall off followed by a reach round to a ledge, whabovich was the top of the flake followed by a committing lurch upwards.

Our Father became a touchstone of hard climbing, widely regarded as the hardest rock-climb in Britain and arguably in the world. Certainly, climbers travelled from far and wide to attempt it with a lot of failures. Not surprisingly, Jack Street made the second ascent and I think, Richard McHardy the third.