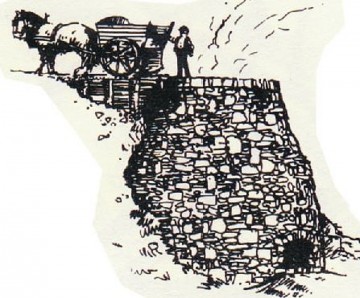

Lime Kilns

Lime kilns were a major feature of the village until the 1960’s. There are remains of three kilns left in the village including the parish kiln used by farmers for lime to spread on their fields.

Burning lime was a very unpleasant activity producing much smoke and poisonous fumes. The practice oddly described in ‘Whites 1857 directory of Derbyshire’ rather romantically states

The wild scenery of Middleton Dale is often greatly improved in picturesque effect, by the fires of the lime kilns, which are numerous

Because it is so readily made by heating limestone, lime must have been known from the earliest times, and all the early civilizations used it in building mortars and as a stabilizer in mud renders and floors. Knowledge of its value in agriculture is also ancient.

Loading

The common feature of early kilns was an egg-cup shaped burning chamber, with an air inlet at the base known as the eye, constructed of brick. Limestone was crushed (often by hand) to fairly uniform 20-60 mm (1 to 2.5 inch) lumps – fine stone was rejected. Successive dome-shaped layers of limestone and wood or coal were built up in the kiln on grate bars across the eye. When loading was complete, the kiln was kindled at the bottom, and the fire gradually spread upwards through the charge. When burnt through, the lime was cooled and raked out through the base. Fine ash dropped out and was rejected with the riddling (larger waste material).

Burning

Only lump stone could be used, because the charge needed to breathe during firing. This also limited the size of kilns and explains why kilns were all much the same size. Above a certain diameter, the half-burned charge would be likely to collapse under its own weight, extinguishing the fire. So kilns always made 25-30 tonnes of lime in a batch. Typically the kiln took a day to load, three days to fire, two days to cool and a day to unload, so a one-week turnaround was normal. The degree of burning was controlled by trial and error from batch to batch by varying the amount of fuel used. Because there were large temperature differences between the center of the charge and the material close to the wall, a mixture of underburned (i.e. high loss on ignition), well-burned and dead-burned lime was normally produced. Typical fuel efficiency was low, with 0.5 tonnes or more of coal being used per tonne of finished lime (15 MJ/kg).

More Articles

| Previous | Lead Smelting | |

| Next | Limestone Quarrying | |

| List all | Local Industries |

No Comments Yet be the first to respond