A rather romantic description of Stoney Middleton from 1872

In 1872 the ‘BLACKS TOURIST GUIDE TO DERBYSHIRE’ was published. He wrote at length about Stoney Middleton, stating: ‘The village is remarkably picturesque’

The full article has been reproduced below, all grammar and spelling have been left unchanged.

STONEY MIDDLETON.

Inns.—Moon ; Lover’s Leap ; Grouse ; Miners’ Arms. From Bakewell, 6 m. ; from Castleton, 10 m. ; from Haddon Hall, 9.m.

STONEY MIDDLETON is a large mining and agricultural village in the High Peak. The manor belonged at an early period to the Chaworths, under whom it was held by Bernake, who sold it to Furnival, from whom it passed to the Cavendishes. The church, a curious octagonal building, contains memorials to Finny and others. There are also dissenting places of worship and schools.

The HALL, the seat of Lord Denman, is a picturesque building near the church. It was long the residence of Chief Justice Denman, who was raised to the peerage by the title of Baron Denman.

The BATHS are near the church, and are said to be of Roman origin, and to have been dedicated to St. Martin. The water is tepid, and the baths are beautifully situated in a quiet sylvan spot, shaded by trees, and the grounds intersected by winding paths. “That this bath was established by the Romans may not be easily established at this remote period of time; but when we consider that they long occupied this part of the kingdom, and that the use of the tepid bath was probably introduced by them into this country, the opinion appears not altogether groundless.”

The village is remarkably picturesque. “About the centre of the village is the toll-gate, a characteristic little modern Gothic octagonal building, resting upon arches, beneath which the stream, after running the entire length of the dale, empties into a large mill-dam. The village mill, worked by a ponderous overshot water-wheel, has recently been rebuilt apparently in such a style of superiority and convenience as is but seldom seen. The view from the centre of the village near the toll-bar is picturesque in the extreme; immediately in front of us is a steep rough ascent leading to the upper part of the village, on each side of which the cottages are seen rising tier above tier in the wildest confusion, and built in such nearly inaccessible places as would almost seem to preclude the possibility of their being approached. In some places the solid rock has been cut away to admit of room on which the buildings might be erected, while in others, outhouses have literally been scooped out of the immense stony masses, and the doors of some of the residences may be seen opening above the chimney tops of others.

Intermingled with the houses are projecting masses of rock, from which tall trees in some places grow out in wild profusion. To our left is the toll-grate, where two roads converge; the one leading by the village cross to Baslow, etc, and the other to the lower part of the village and the church.

Immediately behind the house from which we are examining this striking view the rock rises perpendicularly above the roof to a considerable height, and frowns down upon the valley below in majestic silence, bearing on its crest, immediately over our heads, two chapels and several cottages, between which a rugged and steep path ascends to the top of the cliffs, while to our right the wild majestic dale opens its rocky portals, beneath which the houses appear to nestle for shelter and warmth, to receive us.“

MIDDLETON DALE is a long narrow vale with a rapid stream running through it. “The glory of Middleton,” says Mr. L. Jewitt, in “Nooks and Corners of Derbyshire,” “is its Dale, at the opening of which the rocks gradually rise in all their nakedness, on the right towering above the houses, whilst on the left the rugged slopes are thickly wooded between the habitations. On entering the Dale, the first grand object which attracts attention is the celebrated rock called the Lover’s Leap, rearing its bold blackened front perpendicularly to a prodigious height above a substantial inn bearing the same name, kept by ‘mine host’ Mason, romantically situated at its base. The circumstance which gave rise to the singular name—the Lover’s Leap—by which this rock is known, occurred in about the year 1760, when a love-stricken maiden, named Hannah Baddeley, finding that her affections were not returned by a young man to whom she was madly attached, and who instead treated her with coldness and disdain, in a moment of deep despondency and despair threw herself from its summit, in the hope of destroying her life, which had become so burdensome to her. Her fall was, however, fortunately broken by some small trees which grew out of the crevices, and she fell into a sawpit in an insensible state, where she was found, and having been removed home, gradually recovered from the serious injuries she had received and although she was crippled ever afterwards in consequence, lived a single end most exemplary life for about two years, when she died. In the church-yard a mutilated and almost worn-out gravestone shows the place of her burial; and although the inscription is now nearly obliterated, the spot is well remembered by the villagers, who almost seem to venerate the memory of this melancholy love-martyr.

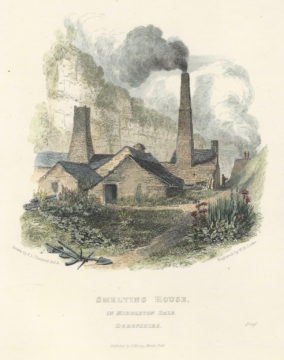

“From here masses of rock jut out one above the other all the way up the dale on the right hand side, while on the left the steep ascent is for the most part covered with herbage, with here and there circular masses of solid masonry, used as lime kilns, and whose strong archways and tower-like fronts give them a castellated appearance, and remind us of the strongholds of a race of giants, A little way above the Lover’s Leap are the Barytes Works, where that material, having been ground, washed, and afterwards bleached with vitriol, is converted into white paint; and adjoining is the lower Cupola, or smelting works, for extracting the lead from the ore. Opposite this is the Grip, an opening between the rocks, leading by a steep and dangerous ascent to the cliffs above.

“Close to the Grip a giant Tor rises perpendicularly to an immense height, towering above the dale in absolute awe and majesty, and, unlike most of the rocks in the dale, its broad front is almost unbroken, and appears as one compact and solid mass; one portion being thickly overgrown with ivy, seems but to render the appearance of the rest more sterile and bare, and, contrasting with its cold grey front, seems to add to its solemnity and grandeur; up its sides grow tolerable trees, while tufts of grass fringe the ledges formed by the almost horizontal lines of strata, and thousands of martens flit to and fro, and keep up a continual chirping as they light on their suspended nests.

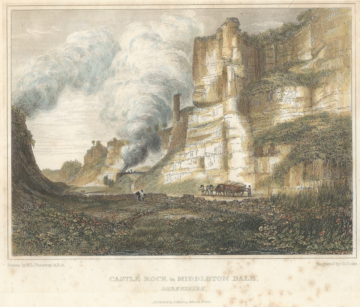

From here the chain of rocks continues forward to the glory of the dale, the Castle Rock, standing out in front of the rest, the intermediate space being crowned by sloping greensward, through which enormous pinnacles of the massive rock rise up perpendicularly towards the sky. The Castle Rock is of immense height, and is not inappropriately named, for its front is flanked by two tower-like projections, spreading gradually out to their base like natural buttresses. About mid-way up its front is a narrow shelf of rock, leading to a sort of natural alcove, called the rock garden, which venturesome people sometimes visit. Above this, growing out of a small cleft in the face of the rock, is a large ash tree, spreading out its branches, and affording shelter for numberless birds, whilst below a portion of the bold projections are overgrown with luxuriant ivy.

“From this point the strata of the rock is very distinctly seen lying, layer above layer, almost horizontally, and seeming to the eye as though, in the first formation of the earth, the great hand of a giant builder had carefully spread out one course of liquid stone, and having levelled it, and smoothed its surface, had, after it had become hardened, again poured over it course upon course, and thus continued his work until the enormous pile of rock was complete; or like layer upon layer of lava, as if it had flowed out in a stream from some gigantic crater on successive eruptions, burying in its course the thousands of living animals which still remain petrified on the surface and sprinkled over the broad front of this piece of regular natural masonry.

Beyond this the rocks again fall back from the roadway, and one turret or pinnacle rises high up in the air far above the rest, like the watch- tower on a castle wall, and so completely is it detached from the rest of the rock, that the clear blue sky can be distinctly seen through the cleft on its side. On this point of rock more than one daring person has, with consummate foolhardiness, we are told, stood on his head; and it is related that one of the villagers, in a drunken frolic, having enlisted into the army, was, in a more sober mood, desirous of withdrawing his rash promise; upon this, the officer offered that if he would stand on his head on this frightful pinnacle he would give him his discharge; this, to the astonishment of all, he did, and having descended in safety, was rewarded by having his liberty granted.

“Under this rock the stone has been quarried very considerably, and large mounds of the waste material, overgrown with grass, now cover up its base, and in one portion of it is a cavern, which, if at money-making Matlock, would be made quite a fortune to the owner. A little beyond this point a deep chasm or cleft separates the rock from crown to base, as though cracked in two by some mighty convulsion, and in front a clump of luxuriant trees contrasts strongly with the whiteness of the rocks and adds in appearance much to their imposing altitude.

A little farther on is a cavern, known by the names of “Carl’s Work,” and “Scotchman’s Hole,” in the lower part of the solid perpendicular face of the rock. In this cavern the water sometimes rises to a considerable height, and rushes out into the open dale; this circumstance was the cause of the discovery of a murder committed here about a century ago, for the torrent which rushed out carried into the dale a human foot with a shoe, on which was a silver buckle. On the subsiding of the waters a careful search was made, and other remains of the unfortunate man discovered; the finding of the buckle, and other circumstances, led to the identification of the body, which proved to be that of a well-known rich old Scotch pedlar, who was in the habit of passing through the place, and who, it appeared, had been murdered at one of the inns of the village where he was staying; this is one of the current traditions of the village. Above this the bleached crest of the rock rises, tier above tier, to an immense height, its summit fringed with shrubs and grass, and a little higher up the dale crested with a fine clump of lofty fir and other trees, which skirt the surface for some distance, until the bold crest of ridge rocks rise above them.

A little farther stands the Golden Ball, a quaint, solitary road-side inn, at the corner of Eyam Dale, behind which the rocks rise one above another, and form an acute angle of tower-like proportions, of the most sublime character. The opposite side of the entrance to this beautiful dale is also rocky, but of much less altitude, and completely covered and hidden by a thick plantation of trees. From here Middleton Dale continues towards Castleton, while opposite Eyam Dale a road winds up the steeps to Middleton Moor, and at this point are ranged a series of lime kilns, of immense size, the smoke which arises from them curling upwards, and forming itself into light blue vapoury- looking clouds, wreathing fantastically about the rocks, and adding much to the gorgeous effect of the whole picture. A little higher on the right a sweet: valley, with rocky posterns and wooded heights, opens up to that holy and classic spot in village history, the Delph, at Eyam, which we have before described.

“Passing this spot the dale becomes more contracted, the sides sloping steeply and precipitately, and covered with grass and small trees, while from the top, on the right, ‘masses of rock jut out and rise at almost regular intervals, and are fringed on their summits with forest trees, amongst whose branches hundreds of rooks and daws congregate.

Here the road winds around the base of the rocks, and after passing the upper cupola, or lead-smelting works, where hundreds of tons of pig-lead may be seen piled up around the picturesque and quaint-looking buildings, follows its onward course through the beautiful valley, winding and threading its way amongst rocks and woods, and keeping up a close companionship with the rippling stream, which funs sparkling by its side.”

No Comments Yet be the first to respond