Mick Ward

Tales of Windy Ledge

By Mick Ward

This text of this article first appeared on the UKclimbing website in 2010.

In 1968 the late Tom Proctor went up to Windy Ledge and attacked the vicious, outrageously undercut flake right of Scoop Wall. Geoff Birtles said The Lord’s Prayer and seconded. Proctor and Birtles had climbed Our Father the hardest route in Britain.

Today it’s hard to convey the magnitude of their feat. In the 1960s there were no cams or wires. The only nuts were drilled-out garage nuts. Most people climbed in big boots because rock-climbing was still viewed as being part of a mountaineering apprenticeship. A runner every thirty feet was good going. If you fell off, the risk of injury was high. VS was for the elite, HVS and Extremely Severe (usually E1) were for gods. Yet Proctor and Birtles had delivered an E4 6b, with a V5 start. There were only two pieces of protection on the main pitch. Neither is bombproof.Thus was born the legend of Stoney Middleton, home to Britain’s hardest routes. Aspirants flocked to attempt Our Father. For years, they failed. Although some of Proctor’s other celebrated testpieces, such as Wee Doris and Pickpocket, lurked in the quarried bays below, somehow the routes starting from Windy Ledge became the gold standard. Before Malham’s catwalk was invented, Windy Ledge, neatly bisecting Stoney’s finest buttress, became the place to go and strut your stuff or, more likely – and very publicly – fail.

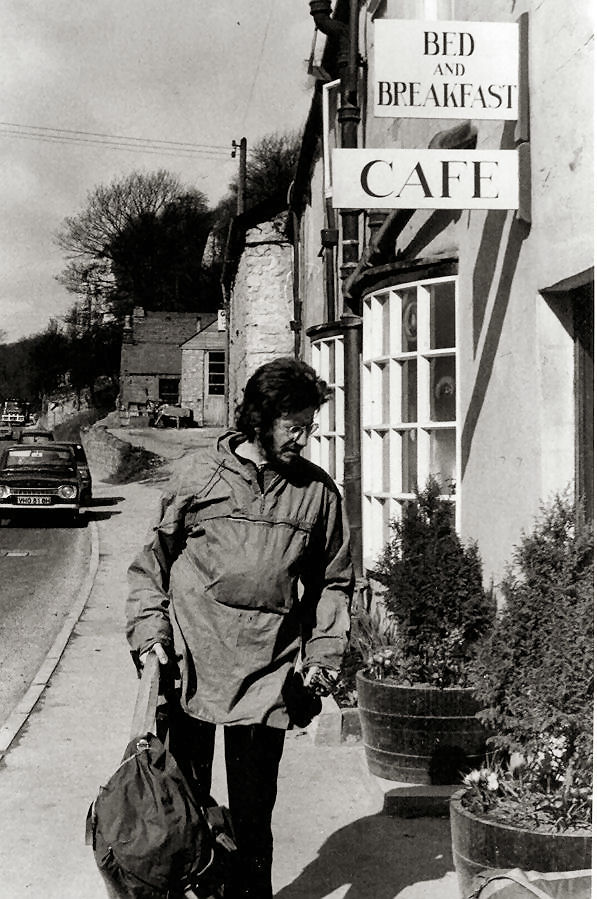

I was first taken to Stoney in 1972. We drove down from Bradford in a battered minivan, shuffled into the dingy café and sipped scalding, stewed tea from chipped mugs. On the crag I fought my way up the lowly-graded What the Hell, appropriately named, in my case, for I couldn’t see what the hell to pull on. A gargantuan struggle continued for over an hour. I was barracked mercilessly from cold, bored seconds. Afterwards, as with so many others, I slunk away from Stoney, vowing never to return.

“Stoney was always about far more than climbing… it was the place to see and be seen. The café was filled with an incessant stream of rock-stars, wannabes and piss-artists.”

Two years later, in the bitter winter of 1974, I came back. With the resilience of youth, VS had mysteriously become HXS and yet Hard Extreme (about E3) was barely entry-level for Proctor testpieces. The late Arnis Strapcans enthused over his Christmas present a copy of the just-published ‘Hard Rock’. In The Moon, Steve Bancroft demonstrated every move on Our Father. To me, this was a revelation: I’d never before met a climber who had the moves so wired. Steve told me about his best mate, John Allen, who, he claimed, really could do the business. And their prowess extended beyond the Peak. The late John Tout had us in fits of laughter, describing an ascent of The Skull on Cyrn Las, which Steve had led beautifully and John had found just about every excuse imaginable for avoiding contact with the rock. “But I was finally forced into climbing the last ten feet!” he dolefully concluded, to ribald jeers.

That night, we settled down in the infamous Stoney woodshed. In my crap sleeping bag, it was agonisingly cold. Pity Steve, who hadn’t got a pit and was reduced to stuffing his jeans with old newspapers. The night seemed endless. You’d nod off, snatch a few minutes’ sleep and jerk awake again, colder than ever. Always there was the sound of Steve’s teeth chattering. Dimly we were aware that, if the chattering stopped, we’d have to get up and do something quite what, we didn’t really know.

The following morning, we propped Steve up on a bench outside the café, in wan sunlight, clutching a mug of tea. By the afternoon, he’d recovered sufficiently to boulder with Proctor on Windy Ledge. But I know now that he could have died that night. You look back, appalled by your ignorance.

“In retrospect, frenetic drinking and partying may not have been the best way to train for Peak horrors…”

Stoney was always about far more than climbing. Slap-bang in the centre of the Peak, home to ‘Britain’s hardest crag’, it was the place to see and be seen. The café was filled with an incessant stream of rock-stars, wannabes and piss-artists. Social standing was dictated as much by finesse in The Moon as finesse on the crag. If you didn’t have finesse – and most of us didn’t – then raw, manic energy might just suffice.

In the memorable words of the late Paul Nunn, Stoney was, ‘a rock-climbers apocalyptic vision of the wasteland.’ Into that wasteland had come the 1960s Cioch Club. No, the Cioch didn’t hearken after mountain glories; the testosterone-fuelled Peak youths were gobsmacked to discover that it was the Gaelic word for breast. Luminaries included the stalwart Jack Street, baby-faced Al Evans, and Geoff Birtles, Proctor’s favourite belay-bunny, and the future eminence grise of British climbing.

A rock-climbers’ apocalyptic vision of the wasteland

British climbing partying reached its zenith in the 1970s. Enough ale was consumed to pickle brain cells forever. Happenings were enlivened by party tricks such as inserting lit matches in one orifice and burning newspapers in another. (The Pex route name Dance of the Flaming Arseholes gives the general thrust.) You’d stagger into the welcoming environs of the café bog to contemplate graffiti such as the celebrated, ‘Oedipus, ring your mother!’, also at Froggatt, courtesy of Proctor. Alternatively you might peruse, ‘Beware the Brothers Grim…’, i.e. Paul Mitchell and John Kirk. If you knew the identities of the graffiti artists, you were probably very well connected.

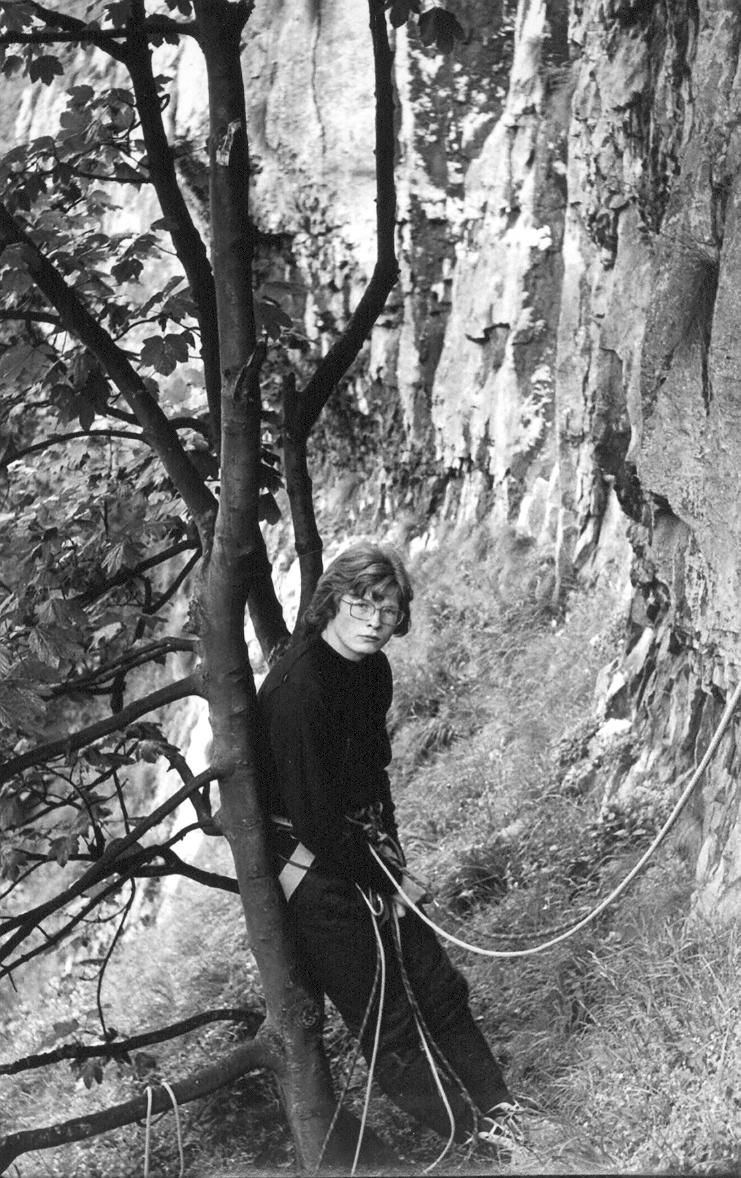

And yet the crag remained daunting. I can remember going up to do Alcasan, the girdle above Windy Ledge, on a dank winter’s day back in the mid-70s. My companion was Dorothy Bogg, probably the best female climber in the country at that time. I glanced at the jumars dangling from Dot’s slim waist and winced. The chilly void was uninviting. Mercifully, in the cold and damp, she desisted and only the historic romp of Aurora’s top pitch separated us from the café’s comforting warmth. The next day we plodded up the hill to Froggatt, started at one end of the crag and worked our way across to the other. In The Moon that night, Dot casually remarked, “It were like a day wi’ Ron (Fawcett).” My heart swelled to bursting and, just once, I felt a man among men.

With the woodshed full to capacity, big teams would head up to Windy Ledge for a night’s kip as close to the fabled routes as you could possibly get. Rolling around in a drunken stupor wasn’t a good idea, while sleepwalking would probably have guaranteed a one-way ticket to eternity. Gabe Regan, one of the stars of the ’70s, particularly relished kipping perched on the very edge of beyond. In the morning, the ultra-exposed traverse of Tiger Trot provided a short-cut either to the café or oblivion. Soloing across it in the wet, savagely dehydrated, with a pounding head, full sac wobbling and muddy trainers slipping wildly, was the stuff of nightmares.

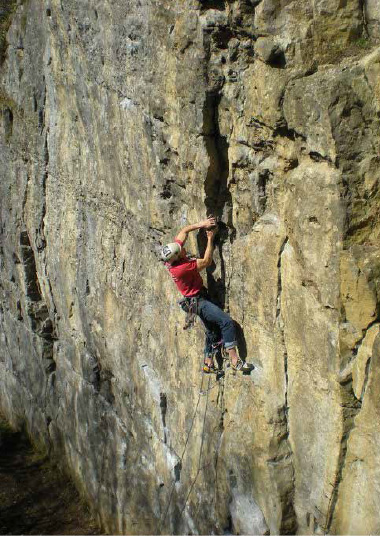

In retrospect, frenetic drinking and partying may not have been the best way to train for Peak horrors. Pity Brian Cropper’s young nephew, Paul, whose tender age meant that he had to be smuggled into The Moon while the beady landlady’s eye was distracted by wily feints. One day, bored by the prospect of yet another extended ‘climbing session in the pub’, the 17-year-old Paul wandered out to the crag for a soloing spree. Warming up on the pumpy Carls Wark Crack and Bubbles, with its nasty start, he went upstairs. Om, Mani and Padme were an aperitif for the precarious crux of Cock A Leekie Wall. A joyous romp up Gabriel/Pearly Gates led to St Peter and thence to Windy Ledge. The polished, insecure Scoop Wall, which proved the most harrowing of the bunch, was followed by the powerful, then crimpy Our Father. Arriving back in The Moon to a raucous, “Where the flamin’ heck have you been, youth?” Paul found his elders well stuck into the ale and seemingly incapable of climbing anything more daunting than a bar-stool.

Tales of misadventure on Windy Ledge

With the way we carried on, helplessly torn between the competing attractions of pub, café, woodshed and crag, it seems unbelievable that more people didn’t fall off Windy ledge. Two who did were Phil Burke and Keith Myhill, doubtless practising for Patagonia’s Fortress. While encouraging Mark Stokes on his efforts to free something on Windy Ledge, the aptly-named Burke stepped backwards and took to the air, doubtless imagining that his career as a motivational guru had literally ground to an abrupt end. Amazingly he survived. By contrast, Myhill soloed up to help a roped but gripped climber reach Windy Ledge, only to find his own footholds disintegrating. He went the length of the crag and was found lying at its base, groaning. Someone ran to phone for an ambulance. Back in those days (Press Button B) things were a lot slower. Growing distinctly bored waiting for salvation, Myhill staggered to his feet and limped off to The Moon. Pint in one hand and arrows in the other, he was contemplating finishing on double-top when the ambulance screamed past, siren blaring. “I wonder who that’s for?” he murmured pensively.

You could fill a book with tales of misadventure on Windy Ledge. I’ll content myself with just a few more. Alison Stockwell’s marvellous little film tells the tale of Black Nick Colton’s meeting with the late Paul Williams. The then-unknown Paul, resplendent in immaculate RAF uniform, was introducing himself to the sleeping population of the ledge by the widely accepted practice of kicking ‘em until you got a response (almost invariably, “F*ck off!”) Amazingly, in the wee hours of the early morning, nobody seemed to want to go climbing… except a severely dehydrated, half-comatose, hungover Nick. Why bother with a warm-up when you could get straight onto the distinctly uphill (and just freed) Scoop Wall? No need to bother with gear when there was a solitary piece of crap tat adorning the bulge. In the end, after fighting the good fight, Nick took to the air for a humungous ride, landing upside-down, with his head a mere foot above the deck. Where was Paul? Dragged high in the air above him, that’s where. If the piece of crap tat had snapped under the strain of the huge lob and two dangling bodies, they’d both have been killed. One thing was for sure: Nick now knew, beyond any doubt, that he could trust Paul. In those days, before modern belay devices, you literally held your mate’s life in your hands.

Another night and Brian Cropper takes up the tale. “We were all dossing on Windy Ledge when someone, I think it was one of the Kirks, decided to go climbing. Up he got and starting kicking his way down the line of pits, getting the usual responses (“F*ck off!”) When he got to Black Nick’s though (can anyone see a pattern here?), Nick nonchalantly riposted, “OK, I’m up for it!” The pair of them headed off for the disused, suicidally loose quarries across the road. (Well, where else would you choose to go climbing in the middle of the night?) All we could see were two pinpricks of light from their head-torches. We sat up in our sleeping bags and bemusedly followed their progress. Suddenly one of the lights dropped, then vanished. Big Sid (Nadim Siddiqui) said, “Shit! Somebody’s copped it. We should go and do something.” But, instead, we just sat around yakking. Amid the darkness opposite, the other light bravely continued. An hour later, the pair of them, covered in muck, staggered back onto Windy Ledge. Nick had dropped his torch but, in true big wall fashion, had carried on anyway. After taking the piss out of them, we settled back for some more kip.”

Some time later, Paul Mitchell (neé Kirk) was giving his all on an attempted ground-up first ascent of the scarily-named Breathing Underwater. Confronted with a steep, uncleaned line, disposable holds and negligible gear, things were certainly getting exciting. As the pump mercilessly set in, options became ever more limited. Andy Parkin was strolling along the path below. “Want a top-rope, Paul?” he yelled up. For once, pride yielded to discretion. “Yes…!!!” Paul eyed his bulging forearms, steeled himself to ignore torture by lactic acid and braced himself for the inevitable delay. Surprisingly soon however, a rope snaked down. Paul scraped through the crux by the skin of the proverbial. Collapsing gratefully beside Parkin, who was sitting idly on the steep grass above, he muttered, “Bloody hell, youth, I never knew there was a belay up here.” Andy chuckled sardonically. “There isn’t!” Paul’s eyes bulged with horror. I think he’d agree that, on this occasion, he’d been trumped by someone whose boldness has since become legend.

As the hedonistic rock ‘n roll ’70s slid into the grim Thatcherite ’80s…

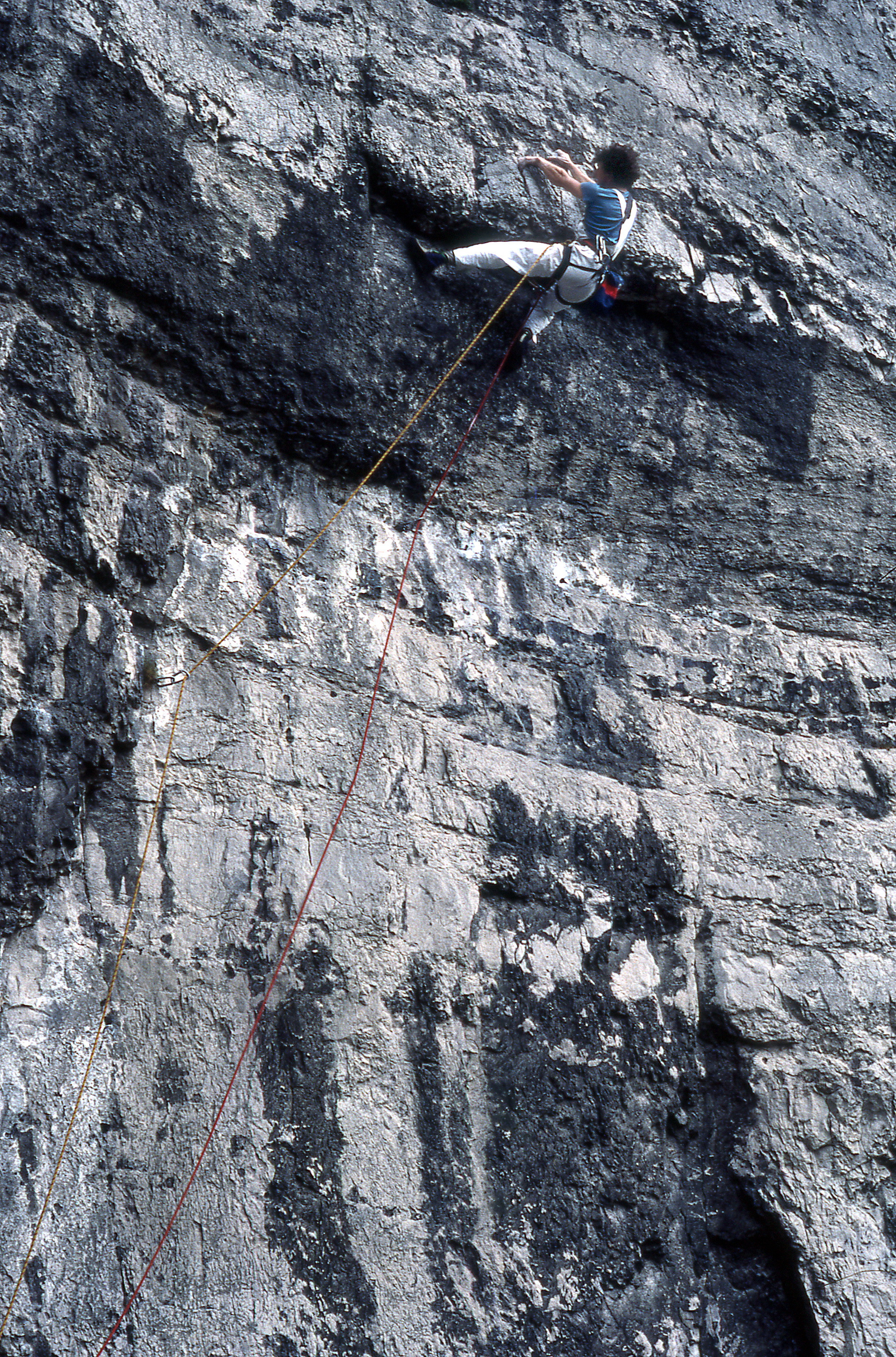

I was to have my own little belaying epiphany on Windy Ledge but we’ll get to this in due course. As the hedonistic rock ‘n roll ’70s slid into the grim Thatcherite ’80s, Proctor made a renewed onslaught on the crag. Circe gave another dimension to the term ‘pump’. Fifteen years later, Four Minute Tiler would receive the definitive accolade (“Bloody impressive!”) from Neil Bentley, one of the strongest climbers of the 1990s. Earlier Al Evans, with a couple of points of aid, had climbed Menopause, reflecting Stoney’s inevitable change of life. John Kirk’s stunning photo of Proctor attempting to free Menopause became a celebrated front cover for Birtles’ cult magazine Crags. But Proctor failed, ripping his tendons in the process. For over twelve years, he had reigned supreme at Stoney. Now his era was over. He turned to caving beneath the dale, leaving the crags to younger, hungrier aspirants.

One morning back then, I watched Mark Stokes glide effortlessly up Our Father. His partner, the late Ed Wood, followed and headed for the crux bulge of Menopause. Ed failed narrowly. Back in the café, he wistfully confided to Sue, the proprietor, “If I’d done it, I’d have been famous…” Shortly afterwards, that redoubtable jackal, Chris Hamper, succeeded on Menopause and Circe. The psychological barrier was broken. Just a few years later, Simon Nadin soloed Menopause on sight, on the basis that “it was 6b and I could climb 6b”. A statement of youth, if ever there was one! Stand at the bottom and look up.

I think you’ll agree that this was an utterly outrageous ascent. Fluff the crux of Menopause solo and there will emphatically not be a re-take.

In the early 1980s, a squeaky-voiced character called Jerry became a fixture at the crag, usually accompanied by his partner, Noddy (Neil Molnar). I can remember grunting my way up something on Windy Ledge with John Bogg in tow. Noddy followed with similar effort, while Jerry sauntered. “He made that look bloody easy!” Boggie accused. “Well, he should do, he’s the best climber in the country,” I shot back. “Who is he then?” “Jerry Moffatt.” “Never heard of ‘im!” Boggie scoffed. “You will do, mate,” I told him. “You will do…”

One person who definitely had “heard of ‘im” was Lancashire climber, Phil Kelly. Not long after Jerry burst into prominence with the second ascent of Strawberries, Phil was at Stoney, chatting to a couple of lads underneath Wee Doris. One of them asked what Phil had thought of Jerry’s photo in one of the climbing mags. “He looks a right stuck-up bastard!” was the forthright response. The lad’s mate (who turned out to be Noddy), piped up, “Nice one – you’re talking to him.”

In 1983, unfit from exams I returned to Stoney. Noddy offered to clip the first runner on Kingdom Come for me. In a not so rare moment of weakness, I acquiesced. Pissing around on some obscure, harder variant to the right, laybacking an overhanging series of disposable micro-flakes, suddenly he lost the plot and started shaking. He had no gear. If he’d fallen, he’d have taken me with him.

I dropped the rope, then shamefacedly wound it around me again. I just couldn’t let him go alone. Seconds felt like eternity before he clipped the peg and normal life resumed for both of us. But it was to be the last time we climbed together. That summer, Noddy took a bad ground-fall in Pembroke and sustained brain-damage. Some time afterwards, he was killed soloing on the Wasted. Noddy was so young, so innocent, so utterly vulnerable that you just couldn’t help your heart going out to him. When he died, something vital crumpled within me. For more than a decade afterwards, when I drove down the dale, I’d look up at Windy Ledge, wistfully imagining that somehow he might still be there.

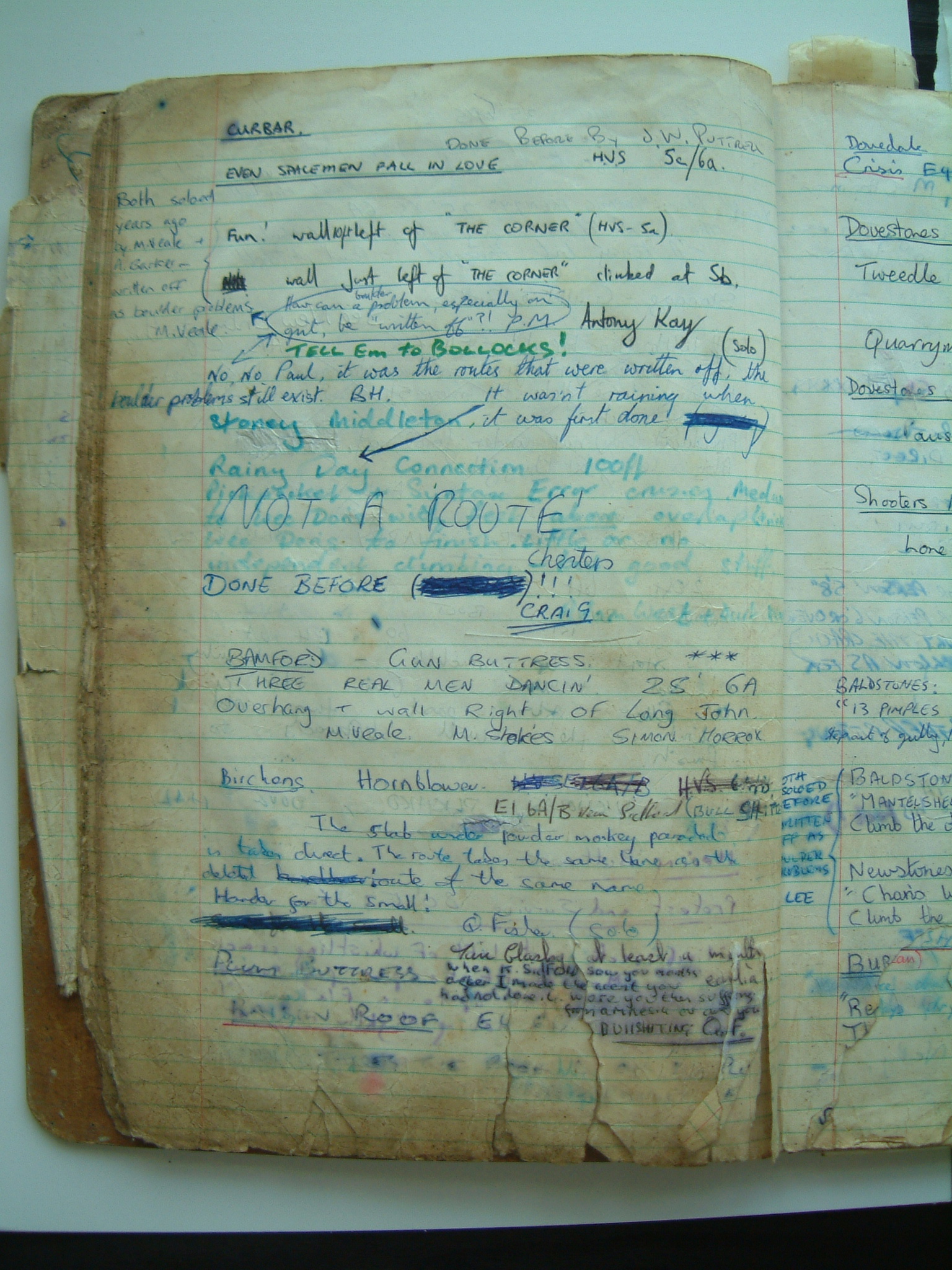

Stoney’s glory days were the mid-60s to the early-80s. When the immensely gifted Dave Kenyon climbed Raindogs, climbers woke up to what was possible at Malham. Ironically Kenyon had trained regularly at Stoney during his formative years, often throwing laps on Bitterfingers. Despite Jerry’s best effort, Little Plum, Stoney just wasn’t steep enough. It couldn’t compete. No longer home to Britain’s hardest routes, its cachet waned. Slowly, inexorably, it slid out of fashion. Like Curbar, it retains a forbidding aura. The routes are combative. People know that, if you’re going to climb at Stoney, you must be prepared to fight.

We need to celebrate the past, not live in it. We’ve shared a few tales of Windy Ledge. There are many more. Stoney was the epicentre of British climbing. A generation of ’60s and ’70s climbers passed through. A few became famous; most didn’t. Either way, it no longer matters. What does matter is that Stoney will always have a special place in our history.

Go to Stoney yourself. It doesn’t matter what grade you climb. You’ll find something to challenge you, something good, something memorable. Stand on Windy Ledge. Look across the dale. Feel the spirit of Nunn’s ‘apocalyptic vision of the wasteland’. Spare a thought for those who went before. And touch the stone.

© Mick Ward 2018

Brilliant, I was there, nervous to introduce myself, I had the feeling I wasn’t good enough. I kipped on the ledge, camped on the grass at Carl’s Walk, slept in the cave that was so cold till I realised it was the drafts from below. My first ever girlfriend joined me camping there.I watched in awe Ron Fawcet traversing on Carl’s Walk, right wards square then left, then corner to corner both ways. Shaking off as he walked off. I still love Stoney, I’ll be there in the morning, Tue 17th Nov 2020.

I think Neil M’s Pembroke accident was 1982, Mick, judging by his brother’s UKC thread. For sure he died July 1983 (same thread and my own recollection).