Boot Making

Boot making in Stoney Middleton was first recorded in 1797 at Pine View, a small cottage off High Street. By the turn of the last century (1900) the tradition of boot making had expanded into family concerns, and became a major industry for the village. The Stoney Middleton factories only produced mens heavy duty working boots including boots for the army in WWI. The village is also home to the invention of the steel toe capped boot.

100 years ago, villages the size of Stoney Middleton, Eyam and Calver would have had at least one shoe and boot maker to keep its population well shod, and would have been capable of making 5 or more pairs each week even that long ago. So why did the villages end up with over a dozen shoe factories employing one third of the adult population as well as most children over the age of 14.

Resources

The area had some natural advantages over many places: a ready supply of good quality cattle from the local farms, good water supplies from the free flowing Derwent River, and a plentiful supply of lime for the leather tannery which was built in Grindleford. There was also plenty of cheap and skilled labour as the silk industry disappeared in the area.

As far back as the 1830s, there were also tanneries in Eyam, Hathersage, Calver, Tideswell and Peak Forest, but these would have been much smaller and supplying local needs only. By 1910 all but Grindleford tannery had gone. It had expanded to supply the whole area with superior quality leather, especially suitable for the heavy working boot maker.

The Tanning Process

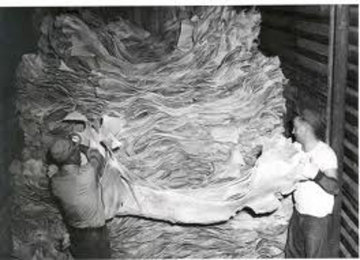

The tanning process has changed little in the last 100 years. Once the animals are slaughtered and skinned, the hides are passed though large vats of lime to loosen the hairs away. After stripping, the hides are washed and dipped in tanning made from oak bark. They are then washed, died, oiled and polished. Heavy skins will have a final dip in paraffin grease for a waterproof finish, making them suitable for use in the heavy work boots traditionally made in the factories in Stoney Middleton.

The Years 1870 – 1910

The early use of simple shoe and boot making machinery made it possible to do more work in less space, this allowed family members to work together and create more jobs for the villagers.

By 1891 around one in three of the population of the local area above the age of thirteen were employed in the shoe factories or working from home.

In 1895 there were half a dozen shoe factories in Stoney Middleton, with many more in Eyam and Calver. The wages paid were less than £1 per week for a 59 hour week, half that of their equivalent workers elsewhere in the country.

The working hours were from 6am to 6pm with unpaid breaks for breakfast and dinner, and then 6am till 1pm on Saturdays. There were no facilities to eat in the factories; workers would have to walk home for their breaks. There were no unions to protect workers rights and workers could be sacked without notice for the slightest misdemeanours.

In many cases the men would have to bring their children to work to make up for the breadline wages in the factories, and skilled workers risked losing their jobs if they did not bring their children to work them. The children were paid around a quarter of the full wage, and women were paid around half the full wage, but often had to work full time in order to earn enough to live on.

Increased mechanisation allowed the larger businesses to work more efficiently, this put more pressure on smaller family businesses to compete for the work. Several smaller factories were forced out of business by the expanding industry in Norwich, Northampton and Leicester. This was despite the better wages paid in those areas.

By 1910 there were three large factories and three smaller ones left in Eyam, and four larger and two smaller boot making factories in Stoney Middleton. Only one remains today. William Lennon in Stoney Middleton continue to produce heavy working boots.

Stoney Middletons Factories

The factories in Stoney Middleton were: Cockers, Goddards (top storey of the Malthouse); Heginbothams at Prefect House (and later in Calver as well); Hinch and Mycock at Dale Bottom; Mason Brothers & Lennon (which moved into the Mill owned by Joseph ) in 1903; and Nugent’s at Craigsteads (formerly occupied by Luther Heginbotham)

Eyam’s Factories

Most of the buildings used as factories in Eyam still remain today. There were seven main factories owned by companies such as Ridgeway & Willis, Robinson’s, West’s, Ridgeway Brothers and Ireland & Froggatt. All the remaining factories have been converted into private housing.

West’s factory was eventually demolished in 1970.

Joseph Heginbotham

Joseph Heginbotham established his family business in 1884 with his sons Luther, Mathew, William, and Harry the inventor of the steel toe cap boot originally made for miners in 1933. The family business had various factories in the village, including Craigstead (1896-97) a brick built factory on High Street as well as what is now Prefect House next to the butchers on The Dale.

The Strike Years 1918 – 1920

In December 1917 John Buckle, an organiser for The National Union of Boot and Shoe Operatives (NUBSO) was asked to help the local factory workers as part of his national role. He held meetings with workers in The Reading Room in Stoney Middleton, and the Bulls Head in Eyam. As a result, in January 1918 the Eyam branch of the union was formed, initially with 43 male and 46 female members. No workers from Stoney Middleton joined the union at first, partly due to intimidation from the factory owners. Many however joined once the branch was formed. By February, most of the workers in the 8 main firms (5 in Stoney 3 in Eyam) had joined the union.

John Buckle described the situation thus:

They work 59 hours week, no bonus paid, and wages were near the bone. The worst I have seen. Can something be done for them? God help them all.

Wages and conditions in the two villages were poor compared to other parts of the country. In Leicester, where the union was strong, men were earning between 75 and 100s (£5) for a 52 1/2 hour week in 1918, whereas in Stoney Middleton they were earning only 36s (£1. 16 shillings) for 59 hours. Women’s’ wages in the local factories were described as ‘near to the bone’, 12- 15s a week for 55-56 hrs. Women in other big footwear making areas could earn 2 to 3 times that much, and for a shorter week.

The vast majority of boot and shoe companies around the country recognised the union and entered into agreements with NUBSO. But in Stoney Middleton and Eyam, the employers’ attitude was hostile. On 12th January, William Slater, the Eyam Branch secretary was given a week’s notice by his employers, Ridgeway Brothers. The firm stated that they would have ‘ no dictation from the union.’ Mr Tom Barber the Branch president was sacked by E. West and Son. In total, at least 11 workers were dismissed because of their actual or alleged union involvement.

The companies refused to meet union representatives, or consider workers requests for improvement in conditions or payment of a war bonus. The union approached the Government to intervene and help avert a strike, but the employers turned down an offer of conciliation by the Ministry of Labour. Because the dispute arose during the First World War, there was an obligation on companies and unions to seek arbitration to resolve differences. The local boot and shoe firms however were unwilling to go to arbitration. It was only after all these channels had been tried that the union resorted to strike action.

Many of the families involved had sons in the forces. At least one of the main firms, Heginbotham’s had produced army boots, and another, Mason Brothers & Lennon was repairing boots for the army. However the union view was that workers returning from the war should be able to expect decent jobs to come back to. Employers shouldn’t exploit the war situation by worsening conditions, profiteering or refusing to recognize trade unions. A strike was a last resort, but in the circumstances they felt they had no alternative.

The strike began in March, with around 160 workers in 8 firms involved. The strikers had 4 demands: Recognition of the union; a reduction in hours to the nationally agreed 52.5 hour week; payment of a war bonus (agreed nationally by the union and the employers’ federation); and reinstatement of the workers dismissed for their union activities.

Taking strike action carried great risks. Workers could be sacked. They could be evicted from their homes as many were owned by employers or their friends. Making ends meet was a constant challenge. Whilst the union paid strike pay, it wasn’t enough to sustain families, and other income had to be sought. Family members who worked in different trades were able to help, and children played a key role e.g. running errands or helping to collect firewood.

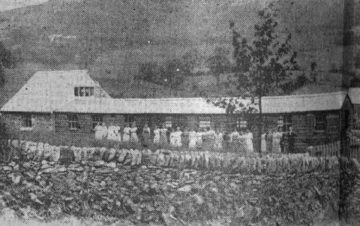

The strikers held regular parades, headed by a local band, to gather support and boost morale. They also issued an appeal to NUBSO branches and other trade unions. They got good support from workers in Sheffield who brought over donations of cash and joined some of the parades.

Strikers and supporters in Stoney Middleton. John Buckle is on the right wearing a bowler hat. To his right, in the trilby hat is Bill Slater, the union branch secretary sacked by Ridgeway Brothers.

Support also came from more unlikely quarters. The vicar of Stoney Middleton, the Reverend John Riddlesden invited the strikers into St Martin’s church for a special service. He preached on the theme of Cain and Abel’s story and its central question ‘Am I my brother’s keeper?’ , appealing to the conscience of local employers.

A local magistrate called William Nixon, who was to play a key role later in helping Stoney Middleton obtain mains water and sewage, tried to bring the sides together. A cutlery employer in Sheffield for over 50 years, Nixon had considerable experience of working constructively with trade unions. He tried to persuade the local employers to meet with union representatives and avoid lasting damage to the social fabric of the two villages. The employers refused and Nixon was exasperated by what he regarded as their out of date thinking and stubborn attitude.

One of the Stoney Middleton firms did agree to have talks. In May 1918, Heginbotham Brothers signed an agreement with NUBSO and the strike at their Prefect House Works was called off. Their pragmatic approach was probably because they’d had war contracts, and to get further contracts they’d need to adhere to nationally agreed pay and conditions. However the other employers refused to settle or accept a further offer of Government arbitration in the summer which followed the intervention of Will Thorne, a Trade Union leader and MP who came to Eyam and asked questions about the strike in Parliament.

The employers thought the strike would crumble in the cold winter months, but the strikers were determined to keep going. They came up with a new idea, to set up their own factory.

The workers and their union raised money for the new initiative in 1919. Donations came from NUBSO branches, Sheffield munitions workers and the Daily Herald newspaper.

John Buckle obtained land in Eyam (just off Tideswell Lane) and an old army hut. The strikers helped to lay a track and erect a stone building for the engine to run the machinery. After a lot of work, the new factory opened in 1920. The aim was to run the works on a cooperative basis and initially about 40 women were employed on union rates and hours.

Their decision to pay Union rates placed extra pressure on the factory owners to settle, but the employers remained intransigent. With the cooperative factory now open, and with many of the men obtaining other work, NUBSO decided to call the strike off. It had lasted nearly two and half years, and is believed to be the longest ever strike in the footwear trade in England.

Although only one company had settled with the union, the strike did lead to better pay and conditions in the other factories, and it inspired workers in other local industries to join trade unions and seek improvements. Sone strikers however were ‘blacklisted’; and had to seek work elsewhere. There were deep divisions in the villages. Some soldiers returning from the war had been used as strike breakers, whilst others supported the union.

The seeds sown during the strike did however eventually bear more fruit. During World War Two, when demand for boots was again very high, the local union branch was re-started and all the four local firms remaining recognised NUBSO and implemented nationally agreed pay and conditions.

THE FULL STORY OF THE STRIKE IS TOLD IN A NEW BOOK ‘The Air of Freedom’ by Steve Bond and Philip Taylor

Copies are available, priced £6 from the Moon Inn, Stoney Middleton, or by post from: The Cordwainer, unit 8, Brough Business Centre, Bradwell, Hope Valley , S33 9HG. (Please add £2 for post and package, and make cheques payable to S.Bond)

Ethel Carlton Williams 1948

In 1948 Ethel visited Stoney Middleton researching for her book Companion into Derbyshire

Stoney Middleton has a flourishing industry-boot-making. There are no fewer than six factories, one is more than. a hundred years old. I asked the advice of a small boy, playing with an old motor tyre, which one I should visit. “Yon’s best,” he said, pointing up the hill – If you take boots there, they come back better than new. This was high praise, so along I went, and found a room crowded with benches, where men were making massive hob-nailed boots. No light ladies’ footwear is made here. Only solid boots, which will last a life-time, and are guaranteed to keep out the wet, even in flood time. The weight of a finished pair is a revelation.

At first the noise seemed overwhelming. The clang of machines driving in rivets; the whirr of sewing machines; the friction of emery wheels, all blended into a subdued roar, yet in the tumult, each machine kept its individual noise. Gradually as my ears became accustomed to the din, I began to watch the process of boot-making. At the cutting table, a man with a sharp knife and keen eye was cutting uppers and tongues from a large sheet of leather. He measured the strip with his eye, laid on the pattern, and cut so that not a scrap of leather was wasted. Next, girl machinists were stitching the sides together, their needles passing through the thick leather as though it were chiffon. Another girl pressed the backs in a machine, while a third inserted the eyelets, which poured down a tube and were fastened into place, while she worked a foot pedal. Meanwhile another machine was cutting soles, and these were joined to the uppers by young boys, who knocked in the nails.

Downstairs heavy machines were completing the process of turning leather into finished boots. Here the clang was deafening. Two elderly workmen, veterans in their craft, were knocking iron “tackets” into the soles in neat rows; a more difficult art than anyone would suspect by watching them. Then came the last stage of all, when the leather was smoothed with an emery wheel, and any fragments rounded off with a sharp knife. The finished products are piled up by the door, and Stoney Middleton may well be proud of its industry, for it boasts that its products are sent to all parts of the world.

Boot Making Today

William Lennon is the only remaining boot factory to survive in the area. They have been making heavy boots for agriculture and industry in the same factory since 1904. Now into their fourth generation, the family company was established in 1899 to service the then burgeoning local quarrying and lead mining industries with quality work boots.

In 2010 The Cordwainer became the first new shoemaking business in the area for 100 years. Located near Bradwell, the Cordwainer manufactures bespoke orthopaedic footwear.

Can You Help?

Local historian Steve Bond and shoemaker Philip Taylor have been compiling information about the shoe factories and the strike, with the intention of creating permanent displays at the new Heritage Centre in Stoney Middleton and Eyam Museum.

We are particularly interested to hear from relatives and descendants of those who owned and worked in the shoe factories, and those who remember the locations and names of the factory owners in the area.

Contact – use the ‘Leave a reply’ section below:

Boot making Eyam

Are you aware of the early 1734 reference to greasing boots and shoes in the Eyam area, using mineral oil found in the area.

Please put me in contact with lacal historian to whom I can send info.

Happy New Year to all

Cliff

Hi Cliff

Thank you very much for your comments.

You could send us the information via the contact us section on the website where you can upload documents.

Many thanks

I have just read the piece on the Boot factory and the Lennons of Stoney Middleton with great interest, my aunt (mother’s elder sister) is Jean Lennon nee Rowarth who married Dennis Lennon, Percy Lennons son.

I have visited her lots whilst she is recovering from a major operation and strangely have spent hours talking about Dennis, Percy and the boot factory recently. Sadly Uncle Dennis is no longer with us but at eighty two Aunty Jean is still full of the old stories, lots of which I had never heard before, then this popped up via Facebook .

Dear Jane

Thank you for your comments. Would your aunt share her memories with us? We could arrange to make a recording or alternatively you might like to write something down which we can add to the website.

My great grandfather was part of the Ridgeway family who owned the shoe factory there. His name was John and he was the second son. My aunts also told me the Ridgeways were architects and surveyors but this is all I know. John married and moved to Sheffield about 1880/1890 and I think they lost touch with his family. I believe there were/are two different Ridgeway families in Eyam. I would love to find out more and perhaps find my ancestors.

Hi, Ms. Kenning, I think that the Ridgeways came to Eyam from the parish of Hope. Ms Valerie Neal and the late Mr Ivor Neal published searchable CDs with Excel spreadsheets of the Eyam and Hope parish registers including lots of Ridgeways. Did your John marry Amy Slater at Eyam on 9 Oct., 1882? If so, he was born 1st August 1857 and baptized at Eyam on 18 Oct 1857 and was the son of Joseph Ridgeway of Eyam and of Charlotte Hadfield (daughter of George Hadfield), who married at Eyam on 2 June 1857. Joseph and Charlotte’s other children included: Jane, Sarah, Clara, Joe, George, and Mary Ridgeway. Joseph Ridgeway was baptised on 7 May 1826 at Eyam, died in 1911, and was the son of John Ridgeway (bpt 28 March 1802 at Eyam)and of Sarah Garlick (married 10 Sept 1820 at Eyam). John Ridgeway was the son of John Ridgeway and of Martha Rowbotham (married at Eyam on 29 August 1796). John Ridgeway senior was born at Grindlow and baptised at Hope on 2 June 1768 and buried at Eyam on 13 January 1824. John senior was the son of Isaac Ridgeway and of Mary Bagshaw, who married at the chapel of Peak Forest on 14 Dec 1749. I think that Isaac Ridgeway’s baptism is missing at Hope, but can’t remember.

There’s another John Ridgeway baptised 1859 son George Ridgeway and Elizabeth Eyre, but this John stayed at Eyam so apparently wasn’t your ancestor.

Hope the above is helpful/of interest. Best, Glenn T.

My grandfather was Frederick Cocker, great grandfather Ezra Cocker both having a boot factory in Stoney. I would love to know more about them. I know the factory burnt down but little else. Any information would be great.

Hi, Ms. Crook, just saw your comment. If you’re on Ancestry.co.uk, your cousin (and more distantly, mine) Robert Clark of New Zealand has a good family tree on the Cockers, using his research, some of mine, and I think some by your other cousin John Collyer, with some comments on the Cocker family’s shoe business. I believe the Cocker shoe factory is also mentioned in the Stoney Middleton millennium book: “Stoney Middleton: A Working Village”, and also in passing on Ms Rosemary Lockie’s Derbyshire Local History webpage. I’m the fellow who wrote the genealogy pages on this SMHCCG website and am also your distant cousin several different ways (your great-grandparents Ezra Cocker and Ellen Cocker (nee Goddard) were both distant cousins of my Hallam great-great-grandfather–Cousin Robert Clark has some great photos of Ezra, Ellen, and some of their children on his Ancestry.co.uk family tree. Also, Frederick Cocker’s wife, your great-grandmother, Charlotte Cocker (nee Furness) was also distantly related to my great-great-grandfather (way way back–our common Furness ancestor died in 1608!). We also share common descent from the Swift and Thornhill families of Stoney Middleton. So, as you probably know, your roots in Stoney and Eyam go way way back. Best wishes, your distant cousin, Glenn T.

Wow! My maiden name is Siddall.. though my Dads mum was a Cocker.. Gertrude, she married Samuel Siddall and moved to Peakdale.. her parents owned a boot making factory in Stoney Middleton. My Dad was telling me today he used to visit a lady when he was a child next to the Moon Inn, I would love to know more please about this family. My Dads aunt who married into the a siddall family did some research into the family and the name Mettam came up.. and one Ann was a maid at a residence of King Edward 1st and borne him a child out of wedlock.. I’d love to know more on this too.

I am interested in purchasing a pair of boots. Have you a contact number please?

I have researched my Ridg(e)way surname for many years, with worldwide contacts. My family were predominantly in Buckinghamshire from 1650 onwards and there may possibly be earlier lines in Devonshire and the north-west of England. I am intrigued with the bootmaker families in the Eyam locality from the 19th century or thereabouts; does anyone have strong connections with these families and their histories please, as my daughter noticed quite a number of gravestones in the church on a visit there a couple of years ago and one of them was the owner/landlord of the pub The Miners’ Arms so I am lead to believe; (very interesting to me personally even if not directly connected !)

I am also a great grandaughter of Ezra Cocker my grandmother being Marion Ellen Cocker the youngest of Ezras children, there is another cousin in New Zealand Owen Cocker who has a hive of information on every aspect of the family.

My great grandfather Stonewall Jackson was a shoe riveter in Stone Middleton. He was born in 1870 and died in1944. His brothers George,Thomas, Henry and Denis were also employed as shoemakers. I have read your article and have learnt so much more about how poor they were and it’s really sad. Stonewalls son Harold was also a shoemaker and shopkeeper. He was my grandfathers brother. When I was at college in Sheffield in the 60s I visited my great aunt Martha who lived at The Bank. What a lovely village!

Good to hear from you Pauline. When I was researching the boot and shoemakers strike, I came across your great grandfather. He was a member of the bootmakers union, NUBSO. He married Clara Barker I believe and the had 3 children, two of whom were also in the trade.

I don’t know where you live but when we’re able to install the memorial plaque to the strikers in Stoney, it would be lovely if you could attend the ceremony/. Steve

Do you make ladies knee length leather boots such as classic style riding boots.

I grew up on “Brookfields” in Calver, where we lived next door to Mr. Felix Holmes and his wife, Nellie.

He owned and ran a shoe & boot making workshop in Eyam, which, I believe, produced primarily high quality ladies shoes – he gave a number of pairs to my mother.

He took us to see his operation in about 1972, but I can’t remember exactly where it was located.

Having done some research, Felix C Holmes was born on 5th June 1895 in Leicestershire and married his wife Nellie (Lloyd) on the 28th September 1918. They had a son, Roy (b. 8/12/1920 in Eyam) who was probably killed in action in 1944 during the 2nd World War.

In 1939, Mr & Mrs Holmes lived in Derby, where he ran a boot-making factory and appears to also have served as an ARP Warden / Firefighter.

He retired after Nellie died in 1973 and the workshop premises was presumably sold.

Mr. Holmes then moved to Catcliff Close, Bakewell, where he died in April 1981.

Mr Holmes was always a strong supporter of Eyam Church, where I believe he helped to fund the restoration of a wall painting which was uncovered during work which was undertaken in the late 1960s / early 1970s.

Mr & Mrs Holmes’ ashes are interred in Eyam churchyard.